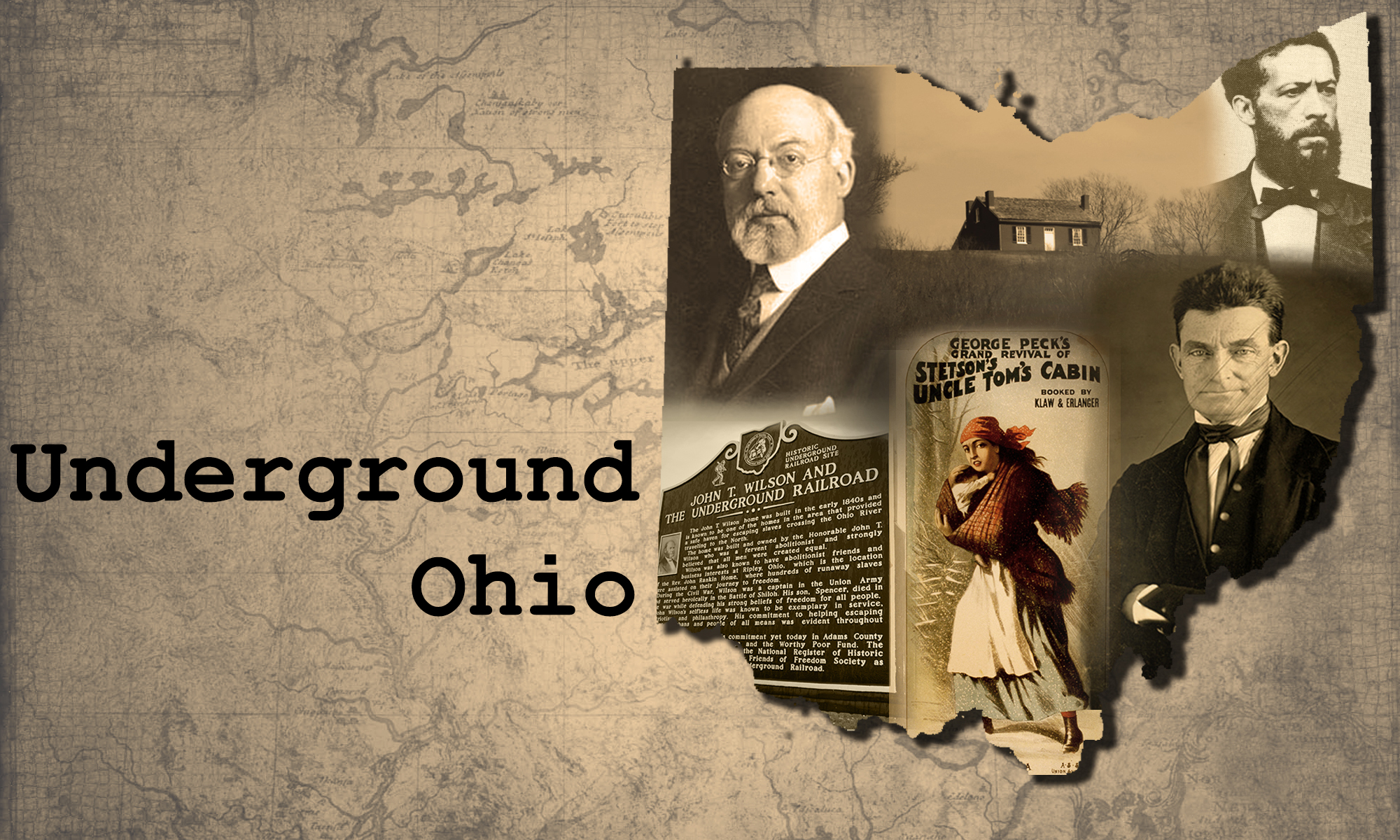

A hub of anti-slavery activity.

A hub of anti-slavery activity.

Founded in 1833 by two Presbyterian ministers, John Shipherd and Philo P. Stewart, the city of Oberlin began as an evangelical community designed to educate teachers and ministers. During the same time, the two ministers formed Oberlin College to further educate the “Godless West,” as they called it.

Founded in 1833 by two Presbyterian ministers, John Shipherd and Philo P. Stewart, the city of Oberlin began as an evangelical community designed to educate teachers and ministers. During the same time, the two ministers formed Oberlin College to further educate the “Godless West,” as they called it.

The Oberlin Heritage Center reports that in 1841, the first three women in the nation to earn their bachelor’s degrees did so from Oberlin College. In 1846, Lucy Stone, a noted women’s rights activist and abolitionist, graduated from the college. Her sister-in-law, Antoinette Brown Blackwell, followed the next year. Later, Blackwell became the first female ordained minister of a recognized denomination in the United States.

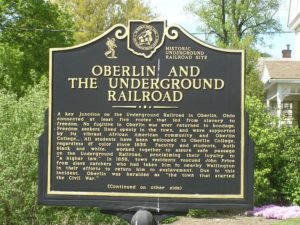

In 1835, Oberlin admitted James Bradley, the first African American to attend the school. Oberlin’s Anti-Slavery Society was formed the same year.

The town quickly turned into a hub of anti-slavery activity. Carol Lasser, professor of history for Oberlin College, wrote about the intersection of religion and politics that created and facilitated the movement in the city in “The Underground Railroad in Oberlin: History and Memory.”

“Opposition to slavery found its expression not only in the election of antislavery state and national candidates but also in the pointed assertions of African American equality,” she wrote. “Oberlin had not only a college that was a pioneer in the higher education of African Americans; it also had public schools that educated white and African American children side by side at a time when the state of Ohio did not require black schooling, much less integrated classrooms.”

Lasser tells of the first documented experience of the Underground Railroad in Oberlin, which was discovered through an 1837 letter. A student formally enrolled at Oberlin College brought a wagon filled with fugitives into the city.

“They took supper in the college dining hall, where students crowded around them,” she wrote. “On the Sabbath, they rested in Evangelically correction Oberlin, and on the following Monday were sent on their way with a guard of students ensuring their safe passage.”

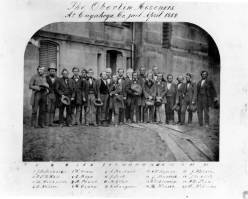

The City of Oberlin reports the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue on its main site, one of the most famous events that occurred in the city.

In 1859, John Price, a free black man, was kidnapped by Kentucky slave catchers and two Columbus deputies. Once word reached abolitionists in the city, men and women went to the Wadsworth Hotel in Wellington, Lorain County, where the kidnappers were holding Price.

When negotiations to free the man failed, the crowd rushed into the hotel and created so much chaos that Price was able to escape.

“Hidden in Oberlin College President James Fairchild’s attic for a few days, Price was then sent on to Canada and never heard from again,” the site reads. “Twenty-seven men who aided in Price’s escape were arrested for opposing the Fugitive Slave Act. While awaiting trial, the men chose to stay in jail and printed the newspaper ‘The Rescuer.’

“On July 7, 1859, the Kentucky slave catchers were arrested and charged with the kidnapping of John Price, and all but one of the twenty-seven men were released from jail and the charges were dropped.”

Liz Schultz, director of the Oberlin Heritage Center, said Oberlin indirectly started the Civil War by encouraging dialogue about freeing slaves and openly sheltering freedom seekers. Watch her and Oberlin College Archivist Ken Grossi discuss the city’s rich history in the video below.

FIRST CHURCH IN OBERLIN

First Church in Oberlin, originally called First Congregational Church, was founded in 1834 as a place where Oberlinans would meet and practice their faith. First Church in Oberlin celebrated 175 years in 2017 after the first cornerstone was laid on June 17, 1842, on the grounds it presently occupies.

The church was built by Richard Bond, a prominent New England architect, whom Charles G. Finney met while recruiting faculty in Boston. At the time, Finney was a newly appointed professor of theology at Oberlin College, where he would later be named the president of the college. Being a renowned evangelist, Finney is said to have drawn a large portion of the church’s congregation.

Members of all faiths and races who moved to Oberlin were absorbed into the congregation. The meetinghouse was the site of many fiery abolitionist discussions, speeches, debates, mournings, trials and rallies. First Church was also a place for celebrations, one of which was on July 7, 1859, when black and white Oberlinans gathered to greet the Oberlin-Wellington rescuers after their long imprisonment in a Cleveland jail. While the city of Oberlin was seen as a safe place for freedom seekers, First Church played an integral role in the city’s reputation.

Below is 360 footage, allowing you to drag and drop your mouse to explore First Church in Oberlin.