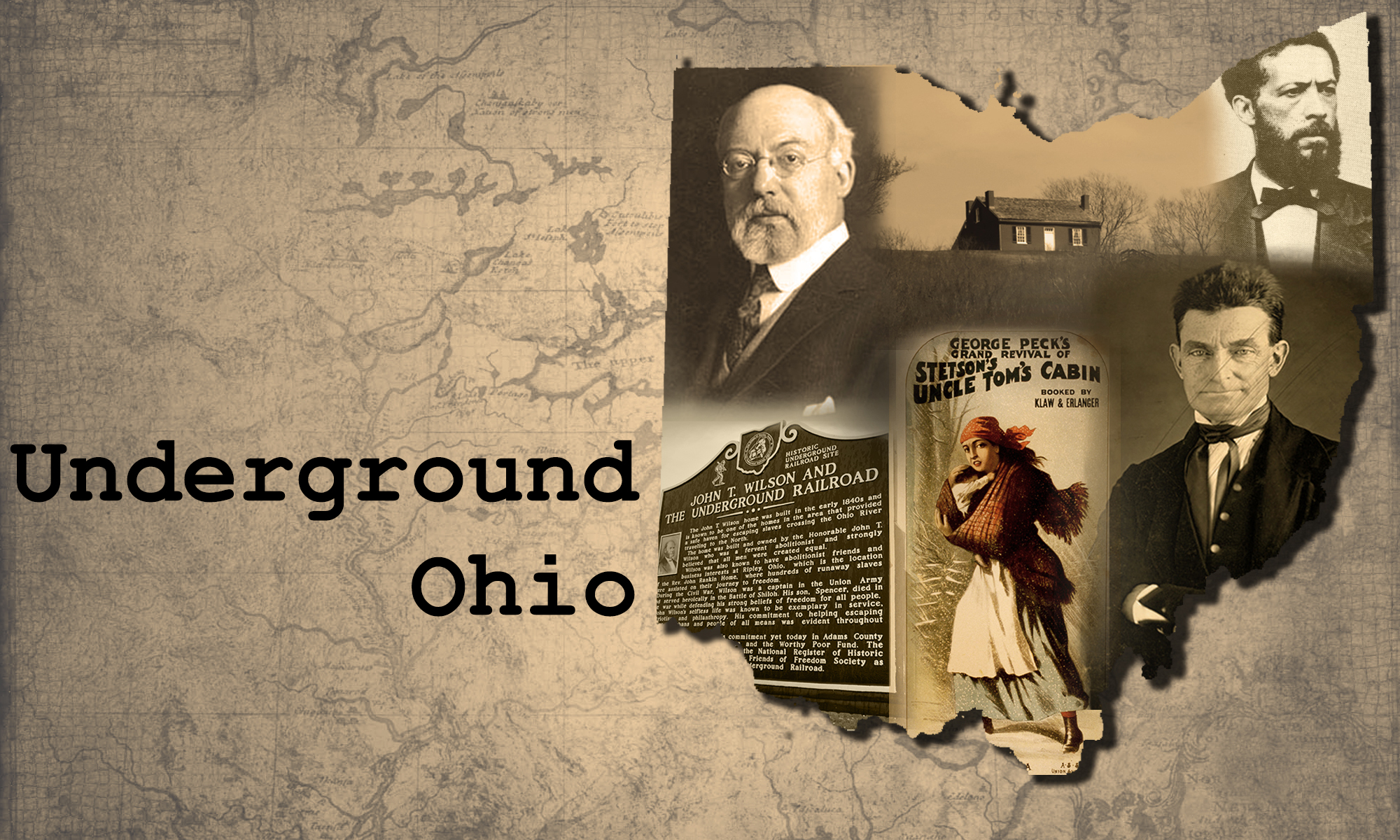

Two of the Civil War’s most celebrated abolitionists.

Two of the Civil War’s most celebrated abolitionists.

No major social movement happens overnight. There are perhaps no greater examples of this than the civil rights movement, and its fledgling beginnings with Civil War-era abolitionists. However, even those abolitionists that we revere most highly are products of decades of gradual progress.

The abolitionist movement is generally categorized into two “waves” that span a total of 300 years. The first of these waves began with occasional critiques of the Atlantic slave trade, with writings dating back as far as the 16th century. This first wave gained traction from the 1770s to the 1820s as substantial numbers of Quaker and Protestant congregations began to embrace anti-slavery discourse.

Many of these early adopters supported such philosophies as gradualism (the slow and steady progress toward slaves’ freedom) and colonization (finding land in Africa for former slaves). Though first-wave abolitionists fundamentally opposed the practice of slavery, these popularized solutions still revealed some discomfort in embracing African-Americans as equal members of the community by illustrating a desire to keep them segmented away from white settlements.

Most of the abolitionists celebrated today are products of the “second wave” of abolitionists, who hardened their stances on slavery and encouraged practices that would lead to the immediate ending of slavery.

By 1833 the movement was becoming more organized, and subsequently accepted, among people in both the north and south. Two of the Civil War’s most celebrated abolitionists, John Rankin and John Parker, encapsulate the culture of this transitory time. Rankin, who was familiar with the backlash against progressive abolitionist views, was considered a key force in reaching “across the aisle” to work with Parker, a former slave whose daring pursuits to extract slaves from captivity exemplified the hardline approach of second-wave abolitionists toward slavery.

John Parker

John Parker is one of Ripley, Ohio’s most celebrated abolitionists. Originally born in the south in Norfolk, Virginia, Parker was sold into slavery at just eight-years-old. Six months later his owner in Richmond, Virginia sold him again to a doctor in Mobile, Alabama, after which he was forced to make the journey to his new owner on foot, chained to other slaves. Later, Parker would cite this instance as the first of many to instill in him a great hatred of slavery.

Parker’s new owner and his sons taught him how to read and apprenticed him in the iron foundries nearby; however, Parker made several escape attempts, provoking the family to sell him. Fearing he would meet the same fate as many others toiling away at plantations, Parker persuaded one of the doctor’s clients, Elizabeth Ryder, to purchase him for which he would repay her with earnings from working at the foundry. A common arrangement at the time, slaves who possessed a trade could be leased out to nearby business for their owners to make money off of them. Anything above the promised amount would be the slave’s to keep. It was through saving his money in this manner that Parker was able to purchase his freedom at 18 years old for $1,800.

Parker traveled north, working for a short while in Indiana before settling in Ohio. In 1848 Parker married his Cincinnati-born wife, Miranda Boulen, and together the two settled in the small, thriving abolitionist town of Ripley, Ohio.

Dewey Scott, The John P. Parker House from JMC – Kent State on Vimeo.

Parker rarely housed runaway slaves in the small brick house he built next to his foundry. A free black businessman with children, Parker had a lot to lose from the penalties imposed by the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Despite this, Parker helped runaways with an even more hands-on approach, frequently traveling into Kentucky to retrieve slaves attempting to escape and leading them back across the river to Ohio, where he would send them along to other “stations” in town (most commonly and notably his neighbor, John Rankin). It is estimated that Parker helped to free 1,000 slaves from bondage, and was notorious in Kentucky for his actions, garnering a $1,000 reward on his head.

Parker’s “war on slavery” as he called it went beyond his involvement on the Underground Railroad. During the Civil War, Parker produced castings for Union soldiers at his foundry and also became a recruiter for the 27th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops.

After the Civil War and the passing of the 13th Amendment to end slavery, Parker spent the remainder of his days focusing on his business. At one point employing 25 men, Parker’s foundry made him one of the richest men in the area. Between 1884 and 1890 Parker obtained three patents, the most notable of which was a part for an improved tobacco press that was in great demand.

John Parker kept a record of every rescue he was a part of, that is, until punishments for those aiding escaped slaves harshened after the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act. It was then that Parker destroyed his records, and he and many other Underground Railroad participants carried out their work in secret. Success often meant there was no documentation. It was not until 1885, when Parker sat down for a series of published newspaper interviews with Frank Moody Gregg, that much was learned about Parker’s countless perilous journeys. Fifteen years later John Parker died on January 30, 1900 in Ripley, Ohio, leaving behind the legacy of a man who overcame his war on slavery through his own success, and the success of those he helped to free.

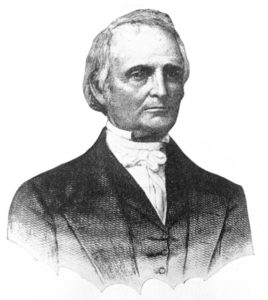

John Rankin

John Rankin became interested in the abolitionist movement from an early age; while a 16-year-old today might just be learning to drive, Rankin was raised in a strict Presbyterian home and began making a profession of religion in his teens. With his intense religious beliefs and the influence of his mother came his staunch disapproval of slavery, and he quickly decided to dedicate his life to abolishing it.

John Rankin became interested in the abolitionist movement from an early age; while a 16-year-old today might just be learning to drive, Rankin was raised in a strict Presbyterian home and began making a profession of religion in his teens. With his intense religious beliefs and the influence of his mother came his staunch disapproval of slavery, and he quickly decided to dedicate his life to abolishing it.

Part of the fledgling anti-slavery movement in America, Rankin formed an anti-slavery society in Kentucky in 1818. Upon moving to Ripley, Ohio in 1822, he found that the townspeople were, by his standards, immoral. He set out to reform the town and while doing so, continued to preach against slavery. When he moved from his home in town to a house on Liberty Hill, he began his work as a conductor on the Underground Railroad and opened his home to escaping slaves, who most often crossed the Ohio River from Kentucky.

Railroad while also continuing abolitionist work with the help of his wife Jean, who would feed and clothe escapees while Rankin was away. One of Rankin’s most influential contributions to the abolitionist movement was a series of letters he wrote to his brother Thomas after learning that he had become a slaveholder. The letters, published as a book called Letters on Slavery in 1826, were widely circulated and became part of the foundation of the abolitionist movement. William Lloyd Garrison, a prominent abolitionist and later Rankin’s friend, was heavily influenced by these letters.